|

|

Last

Modified on

May 07, 2025

A driver uses a phone while behind the wheel of a car on April 30, 2016 in New York City.

Spencer Platt, Getty Images

Text alerts. Spotify playlists. Binge watching. None of these are dangerous pursuits – until drivers interact with them while motoring down the road.

This potentially deadly technological mix has lawmakers across the U.S. rethinking their laws on smartphones in vehicles. The most recent state to act: Georgia, which has a new law July 1 that makes a point of prohibiting drivers from streaming video on their phones while they motor. Drivers can’t hold a wireless device or support one with their body, watch or record video, or text while driving.

Georgia isn’t the only state to single out streaming as a new danger. A Washington state law, the Driving Under the Influence of Electronics Act, in January was the first to specifically mention video on phones. It even makes it illegal for Washington drivers to sneak a peek at their smartphone when stopped in traffic or at a stoplight, though they can touch a mounted or in-dash screen.

Like Georgia, Washington had previously passed a law against texting and driving.

“We are seeing a trend of states amending distracted driving laws to address functionalities of smartphones,” said Jennifer Ryan, director of state relations for AAA’s national office.

Laws in 14 other states – along with the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, Guam and the U.S. Virgin Islands – have banned handheld phone use by drivers. Overall, 47 states have banned texting while driving. Two other states – Arizona and Missouri – ban texting by novice drivers. Only Montana has no law on mobile phone use by drivers.

Despite knowing better, drivers just can’t seem to put down their phones. More than one in every three times a driver gets in the car, mobile phones are engaged, with drivers spending, on average, more than three minutes on their phone during average trips of 29 minutes, according to EverQuote, which tracked 781 million U.S. driving miles last year with its EverDrive safe driving app.

Traffic deaths involving distracted drivers have been a constant concern as more people got smartphones, connections got faster and the ability to do what was once confined to home life – such as watching TV – became an anytime, anywhere pursuit. More than half of all Americans watch video on their smartphones, according to Nielsen.

The driver was watching NFL

The mixture of driving and mobile video can produce tragic consequences. Police said the woman in the driver’s seat of an Uber self-driving car that hit and killed a pedestrian in Tempe, Arizona, in March had been watching “The Voice” on her smartphone.

In October 2017, a truck driver killed a motorcycle driver and injured his sister, who was riding with him, in central Pennsylvania. Police said the truck driver had been distracted, watching an NFL game on his phone and texting during his drive.

The Centers for Disease Control estimated that in 2015 that 16 percent of all crashes with injuries and 10 percent of fatal crashes were due to distracted driving.

“It’s not just texting, (and) it’s not just handheld conversations,” said Jonathan Adkins, executive director of the Governors Highway Safety Association. “It’s Snapchat. It’s video. … These are things we never thought of a few years ago.”

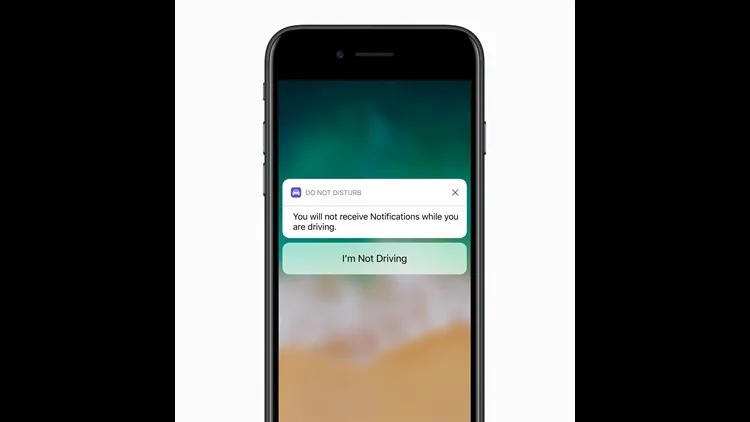

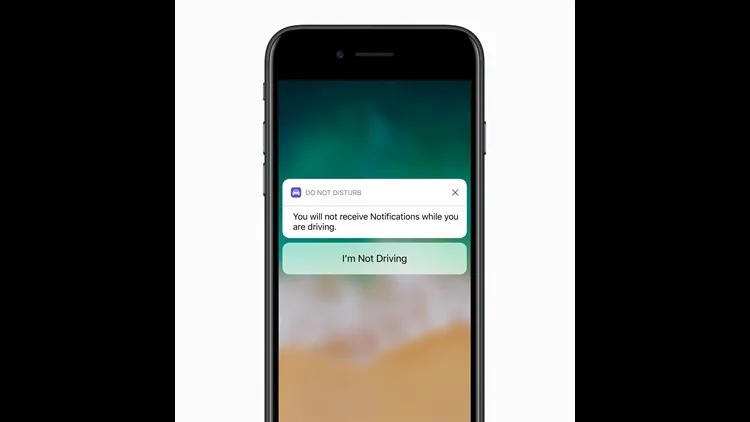

iOS 11 can silence notifications to keep you safe while driving.

Apple

Other nonfatal accidents add to the troubling trend. Last week, a 20-year-old woman in Pelham, New Hampshire, crashed a Jeep Wrangler into a rock wall while her smartphone was open to a FaceTime call.

A tragic fatal accident in April 2015 near Savannah, Georgia, helped build momentum for the state’s updated law. Five Georgia Southern students were killed and two more were injured when a tractor-trailer hit the vehicle they were in on Interstate 16. Their car had stopped for traffic, and the driver of the tractor-trailer said he had been sending text messages prior to the crash.

State legislators looked at insurance and traffic data and found that Georgia’s collision claims rose higher than the national average – despite its no texting law passed in 2010 – and that crashes and fatalities rose 36 percent and 34 percent, respectively, from 2014 to 2016.

Police and highway patrol officers could not enforce the no texting law, “because law officers cannot determine whether a driver is texting or simply dialing a telephone number,” found a report submitted in December 2017 by a state House of Representatives committee.

“It was completely ineffective,” said Rep. John Carson, a Republican from Marietta, Georgia, who chaired the committee and authored the bill.

Gov. Nathan Deal signed the new bill into law last month in Statesboro, the home of Georgia Southern, saying the law’s aim is to “prevent the types of tragic and avoidable deaths that occurred on that stretch of I-16 on that horrible day.”

Carson says he has been contacted about the issue by lawmakers from other states including North Carolina, South Carolina, Pennsylvania and Indiana. Distracted driving is pervasive, he said, because we live in an “instant gratification society. We can’t wait to make a phone call. We have to have instant communication, instant gratification and instant results. That is why we have to look at our cellphones for a text message at a traffic light.”

The new Georgia law does let drivers use hands-free technology to talk and text, use a smart watch or an earpiece to talk on the phone. Some confusion about the law was created when some local law enforcement agencies suggested drivers could not listen to music streaming services such as Spotify and Pandora. Drivers can listen to Spotify and other music services, but they need to start the music before they start driving.

Opposition to hands-free bans has been unorganized or muted, but there is some. In Washington, some residents signed an unsuccessful online petition opposing the law’s inclusion of eating or putting on makeup as a secondary offense. That means officers can charge drivers with that distraction if they are pulled over for something else, such as holding their phone.

In Georgia, legislator Rep. Ed Setzler, a Republican from Acworth, called the bill a case of overreach. “I have a real issue with making people lawbreakers who are safely driving down a stand of road and simply talking on their telephone,” he told WXIA-TV in Atlanta.

Device makers such as Apple and Samsung declined to comment about the issue. But as public awareness of just how attached people are to their phones has increased, tech firms have attempted make it easier to put down the devices while driving.

Apps such as Waze suggest not using while driving unless you are the passenger. Earlier this year, Apple added a Do Not Disturb While Driving feature to its iPhone operating system. The feature sends a message that you are driving to anyone texting or calling you and notifications are muted. Google has created an Android Auto app, which you must download, which hides notifications while you drive and lets you use your voice to answer calls and texts.

Since 2010, wireless provider ATT has conducted a highly visible “It Can Wait” promotional ad campaign to get drivers to pledge not to not use their smartphones while driving. More than 25 million have pledged not to do so on the campaign’s website. And its DriveMode app mutes notifications for drivers.

As more states look to refine their own distracted driving laws, there is some concern among driver safety proponents that laws crafted too specifically could need to be reworked again a few years down the road. “There is a trend with the most recent states honing in on video, specifically, and we are kind of wondering why,” said Annie Kitch, a transportation researcher with the National Conference of State Legislatures.

States may already have prohibited driver interactions with smartphone video in the language of their distracted driving laws, says telecom industry analyst Roger Entner, founder of Recon Analytics. “I think here they are just making it painfully obviously what is allowed and what isn’t allowed,” he said.

In Georgia, the impact already may be evident. Crashes in the state are down 11 percent year to date in the state after rising every year since 2010, says Carson, the law’s author.

That suggests the law’s passage – and spread of information about the deadly 2015 crash – has started changing drivers’ behavior, he says. “It’s made people think, ‘Is it really important to check this message right now?’ ” Carson said. “This is the DUI issue of our time.”